The Royal Society of London

What a historical scientific society has to do with launching start-ups.

Imagine this: It is the middle of the second millennia AD and for the nearly 1,500 years, the center of scientific development and the global economy is not England or the rest of Western Europe… it’s China.

China has given the world gun powder, paper currency, cannons, the magnetic compass, cast iron, and advanced astronomical observatories. China (along with India) up until this period has accounted for over half of the world’s GDP. Western Europe accounted for roughly 1 to 2% of global GDP.

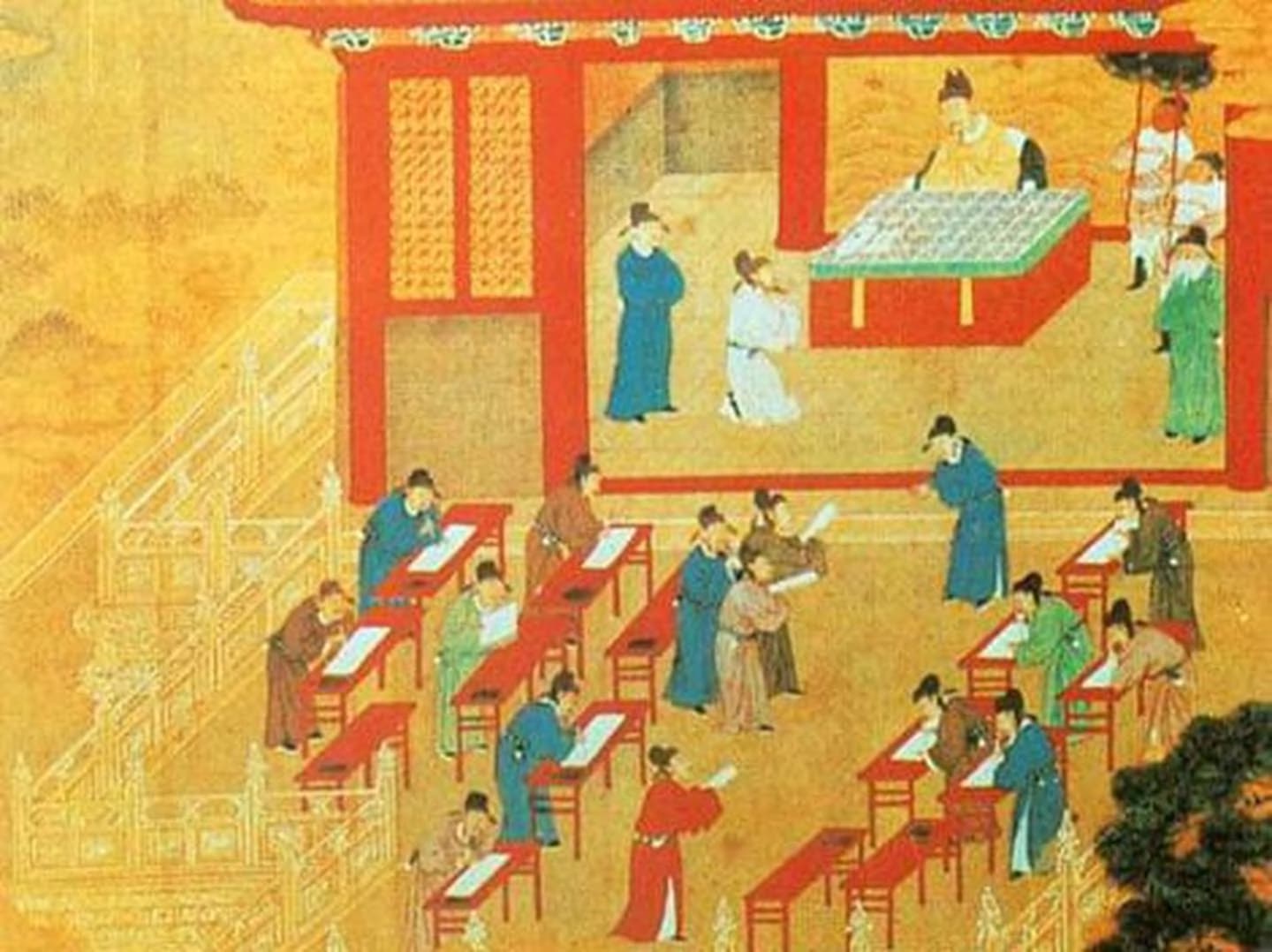

China is years ahead of Western Europe in education as well. By some estimates, China’s population at the time has a 45% literacy rate, whereas, only 6% of England’s population is literate. Nearly a thousand years before England gave us the likes of Oxford and Cambridge University, China had implemented the imperial service examination. With China administering nearly 1 million tests each year — with less than 1% passing — they were able to create a whole new scholarly class.

So, despite all of this, why didn’t the scientific revolution occur in China?

This was a question first proposed by English Academic Joseph Needham and has become to be known as the “Needham Question.”

In Safi Bahcall's book, Loonshots, the answer is really three-fold and conscience between chemistry and history.

Western Europe achieved dynamic equilibrium, which, in this case, means they established channels for the exchange of ideas. European nations did a great job of establishing an exchange of ideas with existing empires, which allowed them to learn a tremendous amount about mathematics from Indian and Arab Scholars. They also learned new technologies from the Chinese.

They focused intensely on phase separation. Phase separation can be defined as the ability to encourage ideas that let countries and businesses run smoothly while also fostering ideas that are fragile “moonshots” that may not work or widely be accepted — all of this while also keeping the ideas separated. The many kingdoms and kings of Europe were willing to spend lavishly on scholars who could help their kingdom grow, giving them whatever they needed in order to succeed in projects that could be considered “too crazy.” This led to the development of the scientific method and the rise of Tyco Brahe, Francis Bacon, Robert Hooke, Isacc Newton, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo, and Johannes Kepler.

They achieved critical mass. With phase separation and dynamic equilibrium, Europe was able to build a critical mass of scholars who, in turn, allowed for the Scientific Revolution to take place in Europe starting in 1543.

China had a critical mass of scholars but did a poor job of giving support to those scholars, their fragile ideas, and the outcomes of their research, regardless if a hypothesis was proven to be the truth or not. China was unmoved in its belief in dogma and the Emperor’s final authority on any and all questions, whereas in Europe, according to Safi Bahcall, “truths were judged by the outcomes of experiments rather than the gavel of authority.”

The Royal Society of London

With the Scientific Revolution in full-swing across Europe, England was able to cement itself as the center of the revolution.

How?

England possessed all three critical elements to launch a successful period of scientific advancement: they had critical mass, dynamic equilibrium, and they pursued phase separation better than any other country in Europe.

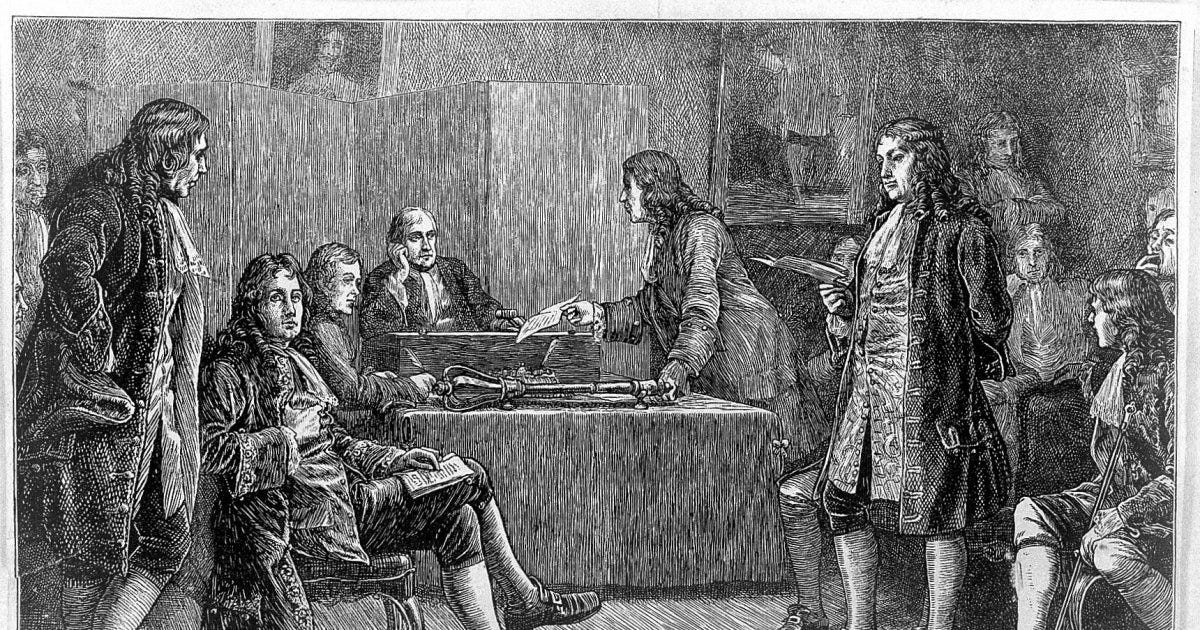

England actively focused on creating these “idea nurseries” where scholars could apply the scientific method to whatever they wanted to explore, then could share the results of their experiments (dynamic equilibrium). The most famous of these nurseries was the Royal Society of London. In Loonshots, Safi Bahcall writes,

“The Royal Society of London, created in 1660, brought together nearly all the founders of modern science in England, including Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, and Isaac Newton.”

These nurseries let founders of modern science pioneer new frontiers without having to operate under the watchful and critical eye of the court of public opinion. Their fragile ideas could thrive or die in peace. That allowed England to grow into the first truly global superpower and become the center of the Scientific Revolution.

The Modern Accelerator

Start-ups, much like the development of the ideas behind modern science, are fragile. Like the Royal Society of London, our modern-day accelerators and incubators have become places where fragile ideas behind start-ups can thrive (albeit in exchange for a piece of the pie) or die (lessons are learned and ideas exchanged regardless if a company is successful).

Everyone has different opinions about the overall validity of accelerators/incubators and whether they generate any meaningful return for the entrepreneur who decides to join an accelerator/incubator cohort. Granted, there are accelerators and incubators that will knowingly take advantage of a first-time entrepreneur, but for the most part, I believe they play a valuable role in the overall start-up ecosystem.

I bring up the history of the Royal Society of London because there are absolutely parrels between this historical society and the accelerators and incubators we see in the start-up ecosystem across the country. If we want the next generation of innovation to thrive, whether that be in Birmingham or the Southeast as a whole, we need to set aside space and the resources necessary to create the necessary phase separation, dynamic equilibrium, and critical mass needed in order for fragile innovation to survive.

Let me know what you think! I would love to hear your thoughts. Don’t forget to share!

-Sean

After a long time, I have read such an amazing blog post.